The Magic of Enzymes

Enzymes are like tiny molecular machines that speed up chemical reactions—without them, life as we know it would grind to a halt. In nature, they do all kinds of amazing work, from breaking down food in our bodies to helping plants grow. Their knack for turning up the reaction speed without needing high temperatures or lots of energy has made them stars not only in biology but also in industries like pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and green chemistry.

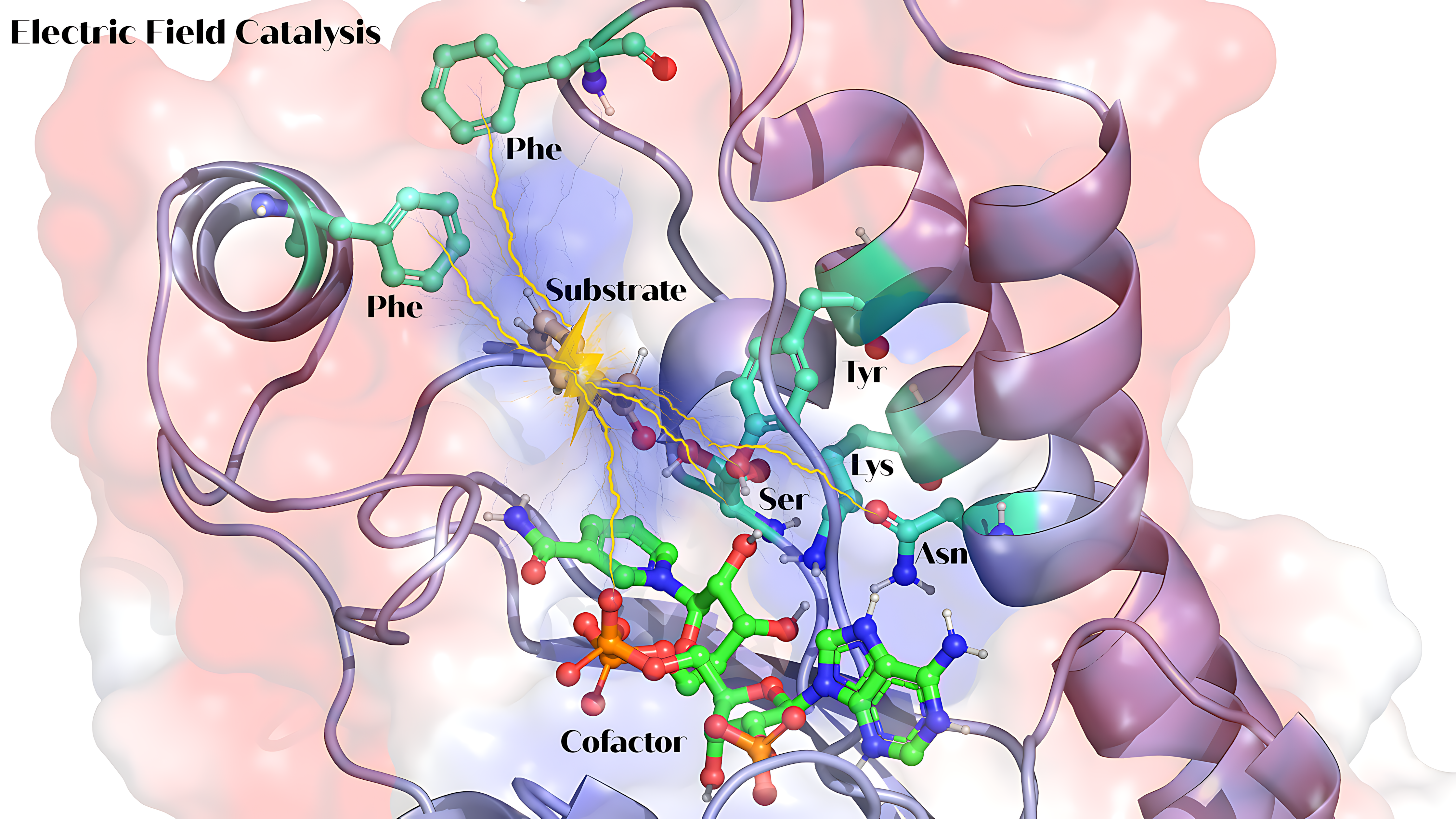

But there is something even cooler going on inside enzymes: they have "electric fields" that can influence how they work. Picture this field as a force surrounding the enzyme, created by the charges and polar groups in its structure. And it is more than just background noise. These fields actually play a starring role in how enzymes catalyze reactions—stabilizing transition states, nudging substrates into place, and even impacting how reactive certain parts of the enzyme are. Tweak these electric fields just right, and you can make enzymes faster, stronger, or even give them new capabilities.

Why Electric Fields Matter in Catalysis

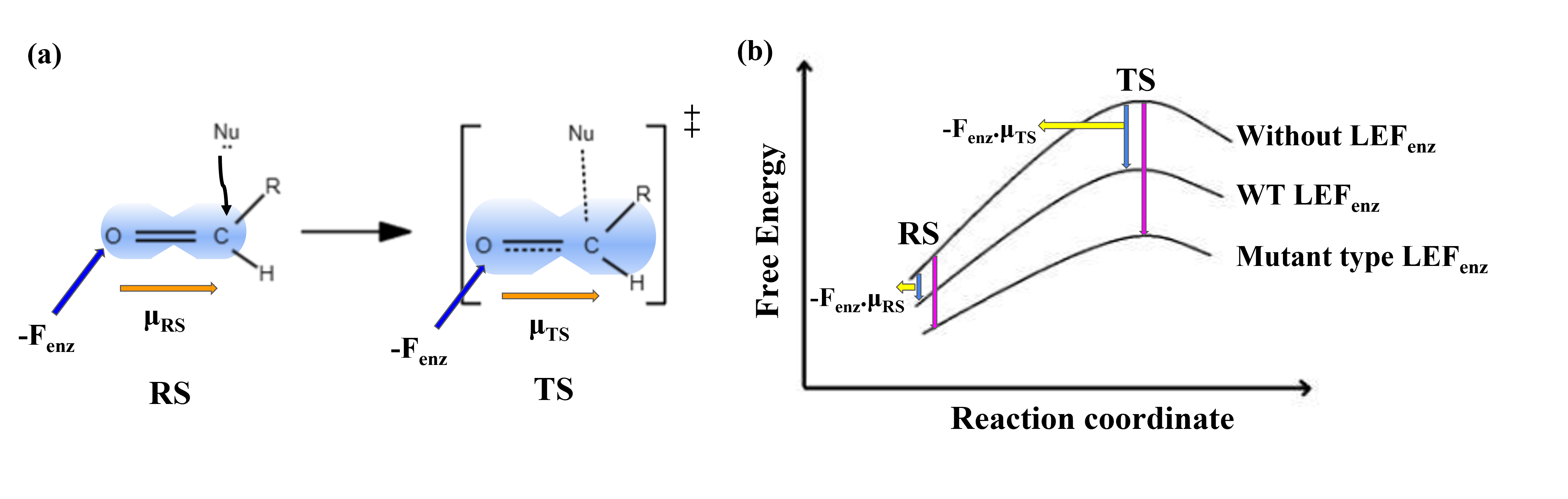

For years, scientists thought enzyme activity was all about having the right catalytic residues positioned perfectly in the enzyme’s active site. But now, we are learning that the zones beyond the active site are just as important. Charged and polar residues around the active site generate local electric fields, which are turning out to be a huge deal. They do not just sit around; they actively stabilize the reaction's "transition state (Figure 1) and can even speed things up.

Figure 1: (a) An aldehyde forms the transition state during a nucleophilic attack. The enzyme's active site exerts an electric field (Fenz) on the carbonyl bond (C=O) dipole, which increases from the reactant state (μRS) to the more charge-separated transition state (μTS). (b) Free energy profiles for reactions without LEF, with wild-type LEF, and with mutant LEF, showing how LEFs lower activation energy and enhance reaction rates.

In simple terms, these electric fields help make reactions more efficient. Think of it as tuning an engine: by carefully adjusting the field, enzymes can achieve efficiencies that make synthetic catalysts look clunky and slow.

How Local Electric Fields Supercharge Enzyme Catalysis

According to Pauling’s famous hypothesis, changing an enzyme’s shape and active site geometry can help lower activation energy. But here is the twist—as discussed enzymes also carry internal electric fields, generated by charged residues in their structure, which can impact the reaction’s direction and speed.

Imagine these electric fields as tiny invisible forces guiding molecules through the reaction process. These fields are created by charged and polar residues, with the charges often aligned along what’s known as the “reaction axis.” This setup creates a dipole moment—a sort of directional force that can influence where and how the reaction flows, much like a compass directing a needle.

So, what role do these fields play in reactions? Well, it is all about Coulomb’s law, which describes the force between charged particles. The strength of the interaction between charges (think “attraction” or “repulsion”) depends on their separation and individual charge magnitudes. The result is a field that can either pull or push on the reactants, helping to nudge them toward a product faster.

To quantify the effect, Scientist often use the idea of an "oriented external electric field" (OEEF). This essentially means focusing the field along the main reaction axis to influence dipole moments as the reaction progresses. The relationship is simple but powerful—changes in energy, or ΔΔE, can be calculated based on the strength of the field (F) and the dipole difference (Δμ) between points in the reaction path:

ΔΔE = 4.8 × F × Δμ ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………(1)

Here, ΔΔE (kcal/mol) is the change in energy difference between the two reference points, F(V/Å) is the OEEF vector, and Δμ (Debye) is the difference in the dipole moment vector between the two points.

A New Era in Enzyme Design

So, what’s the big deal? Well, it means we can now try to "engineer" these electric fields to make enzymes with supercharged or brand-new catalytic abilities. Imagine designing an enzyme that’s specifically tweaked to work better in industrial processes or one that could make drugs faster and more cost-effectively. The concept of engineering enzyme electric fields has opened a whole new world of possibilities.

How We Study These Fields

You might be wondering, "How do we even know these fields exist, let alone measure them?" Enter computational tools like TITAN and TUPA, which let Scientist map and quantify electric fields within enzyme structures. TITAN, for instance, takes inputs like AMBER or CHARMM-compatible files and calculates electric fields at specific point in the enzyme, which helps us see how field intensity and direction impact catalysis. TUPA, on the other hand, is a great fit for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, letting us track electric field changes over time at the active site.

Case study-Enhancing catalysis in the Ketoreductases

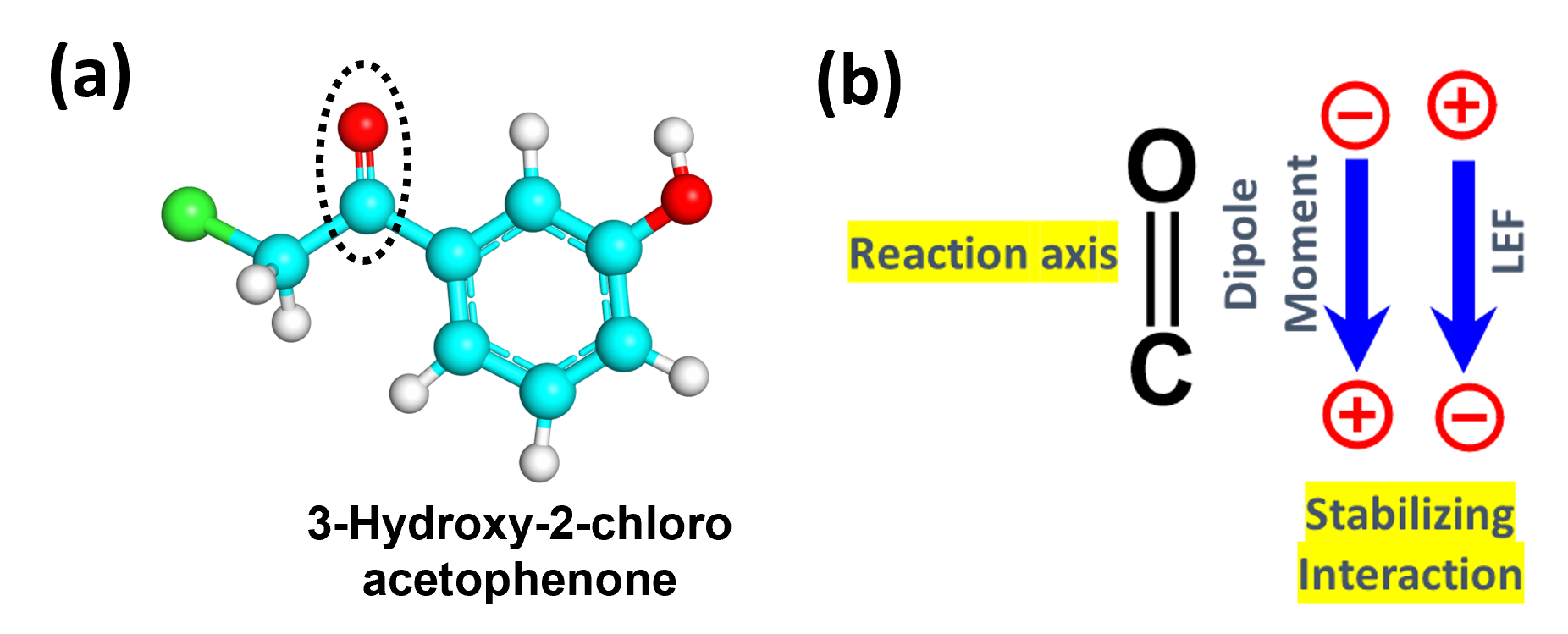

We at Quantumzyme have effectively implemented the application of local electric fields to engineer an QZ ketoreductase enzyme. The reaction of interest involves the NADPH-dependent reduction of a target keto-substrate to its respective chiral alcohol. The reaction axis for this case is defined by the carbonyl bond of the substrate (Figure 2).

Figure 2: a) Structure of target keto-substrate. b) Defined reaction axis by carbonyl bond of the substrate along with the direction of dipole moment and LEF.

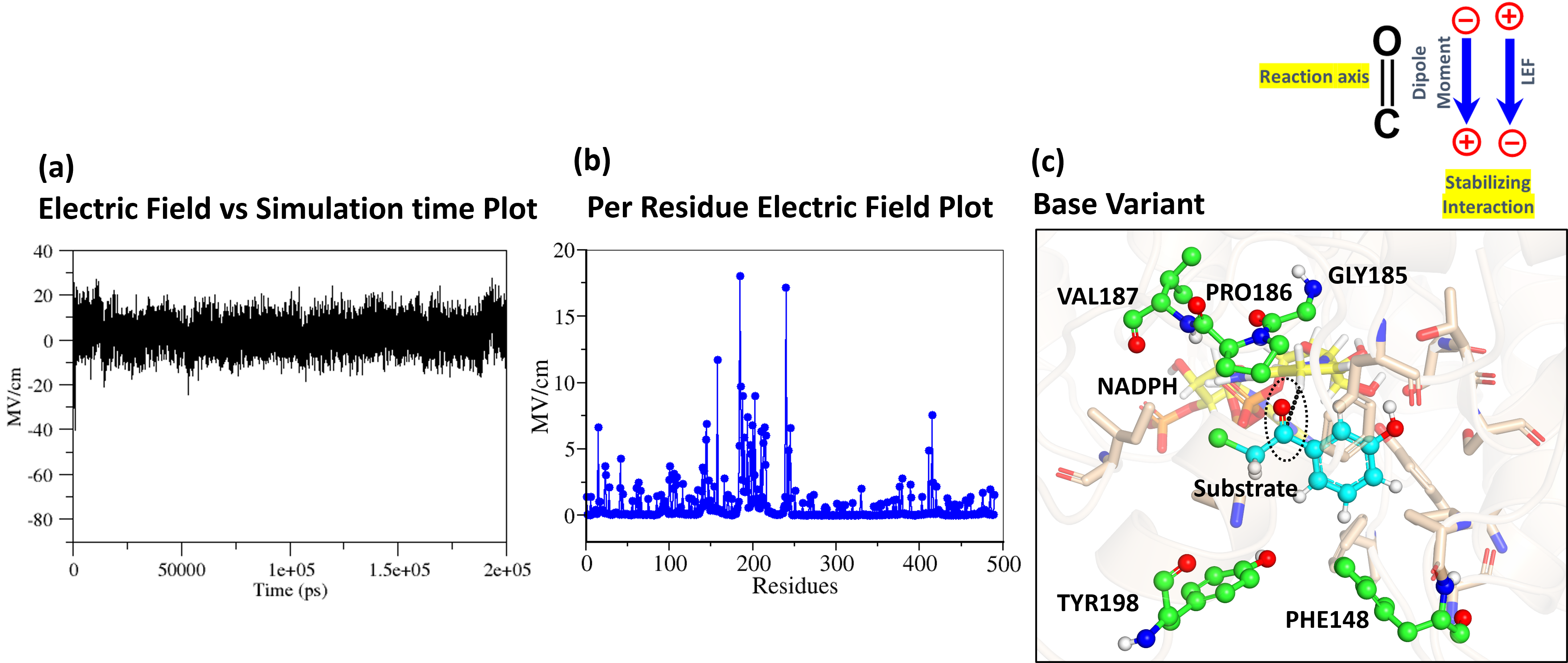

Increasing the electric field at the carbonyl bond of the substrate, decreases the free energy of hydride transfer. Initially, we conducted molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the QZ ketoreductase. The changes in electric field over simulation time and the per-residue contribution to the electric field using TUPA software was calculated (Figure 3a, b). Following MD simulation, we thoroughly analyzed the active site of the enzyme to understand the alignment of residues oriented towards the reaction axis (Figure 3c).

Figure 3: a) Electric field vs simulation plot of base variant. b) per-residue contribution to electric field plot. c) Active site of base variant. Substrate is highlighted in the cyan, cofactor (NADPH) is shown in yellow, main residue aligned towards the reaction axis is shown in green, rest active site residues are highlighted in wheat.

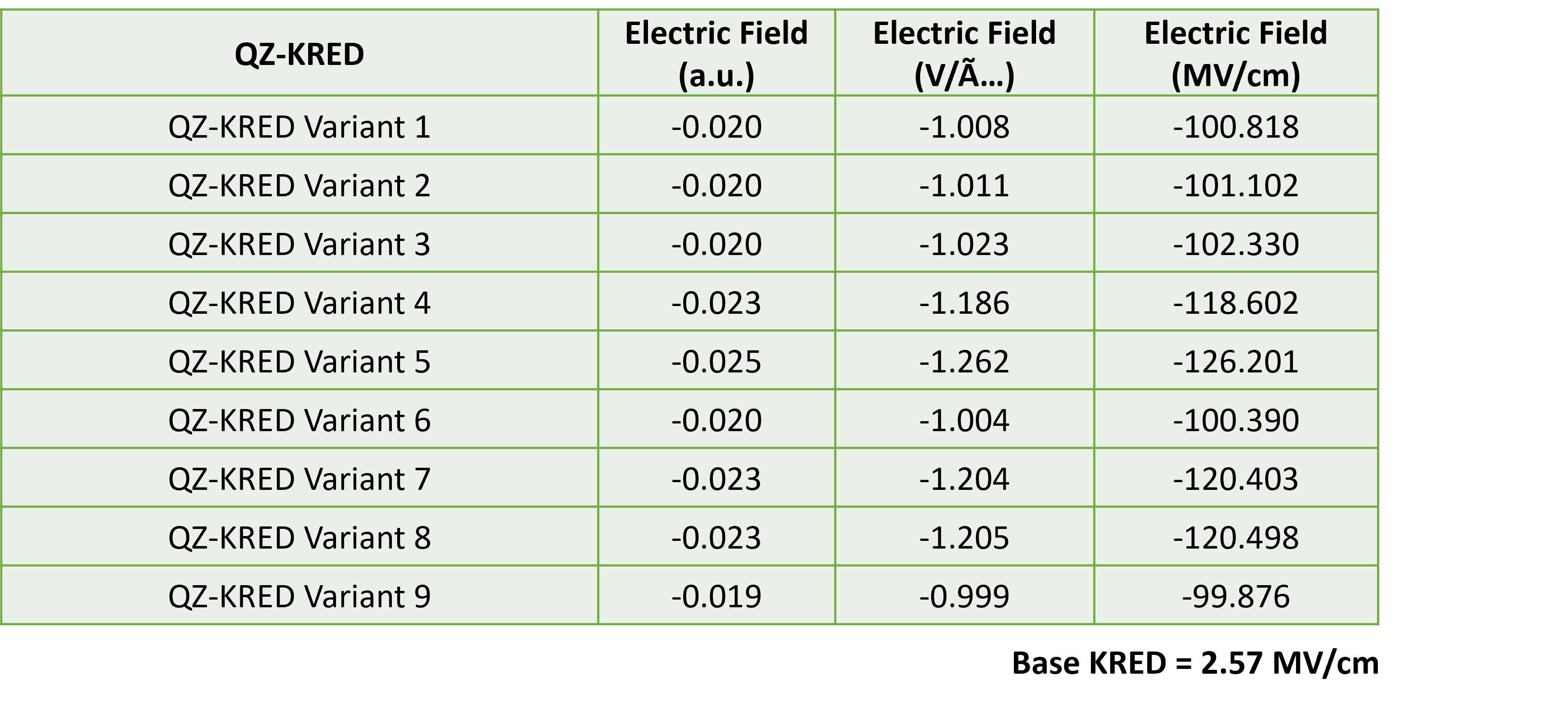

Our analysis revealed that Gly185, Pro186, and Val187 (Highlighted in green in Figure 3c) are oriented near the oxygen of the carbonyl bond of substrate. We therefore mutated these residues to positively charged ones like Lysine (Lys) or Arginine (Arg). Additionally, Phe148 and Tyr198 (Highlighted in green in Figure 3c) are positioned near the carbon of the carbonyl bond of substrate, so we mutated these residues to negatively charged ones like Glutamate (Glu) or Aspartate (Asp). This combination of mutations was expected to increase the electric field along the carbonyl bond of substrate. Utilizing our proprietary QZ-WorkBenchTM, we generated 240 variants with all possible combinations of these mutations. We then calculated the local electric field in all the variants using TITAN software. This approach successfully increased the electric field along the carbonyl bond of substrate, and we shortlisted the top 9 variants. Detailed electric field data is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Detailed electric field data for top 9 variants and the base variant

The Future of Enzyme Engineering

The ability to "dial in" electric fields means enzyme engineering can now reach new levels. By designing and testing enzyme variants in silico, we can boost reaction rates, fine-tune selectivity, and even discover enzymes for reactions that weren’t previously possible. This combination of computational prediction and experimental validation is paving the way for sustainable and economically viable industrial processes.

So, while electric fields may have once seemed an obscure part of physics class, they’re now revolutionizing biocatalysis. With each new discovery, we’re getting closer to a future where enzymes do everything from making greener products to driving high-speed industrial reactions, all powered by the unseen force of local electric fields.

References:

- Ramírez, A. C., Vargas, M. A., & Guzmán, J. C. R. (2024). Bridging the World of Enzymes with Electric Fields. In Chemical Kinetics and Catalysis-Perspectives, Developments and Applications. IntechOpen. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1004072

- Holliday, G. L., Mitchell, J. B., & Thornton, J. M. (2009). Understanding the functional roles of amino acid residues in enzyme catalysis. Journal of Molecular Biology, 390(3), 560-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.015

- Siddiqui, S. A., Stuyver, T., Shaik, S., & Dubey, K. D. (2023). Designed Local Electric Fields─ Promising Tools for Enzyme Engineering. JACS Au, 3(12), 3259-3269. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.3c00536

- Stuyver, T., Danovich, D., Joy, J., & Shaik, S. (2020). External electric field effects on chemical structure and reactivity. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science, 10(2), e1438. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1438

- Zheng, C., Ji, Z., Mathews, I. I., & Boxer, S. G. (2023). Enhanced active-site electric field accelerates enzyme catalysis. Nature Chemistry, 15(12), 1715-1721. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-023-01287-x