Background

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are computer simulations used to study the physical movements of atoms and molecules. These simulations are applied in various fields, such as healthcare for drug discovery, enabling precise modelling of drug interactions and material science for discovering novel compounds. MD simulations have become essential tools for understanding the real world through computers, driving innovation in these sectors. They help build better models of real-world phenomena and predict outcomes, significantly reducing costs in raw materials. One notable application of MD simulations is in enzyme engineering.

Enzyme engineering is a growing field where enzymes are developed for biocatalytic purposes. It leverages MD simulations to explore the intricate relationship between enzyme structure and function at an atomic level. These simulations help identify key residues involved in catalysis, binding, and stability, enabling targeted mutations to enhance enzyme performance. They are instrumental in optimizing enzymes for industrial applications such as biocatalysis, pharmaceuticals, and environmental remediation. By predicting how enzymes behave under different conditions, MD simulations reduce experimental trial-and-error, accelerating the development of highly efficient and robust enzymes.

To achieve these insights, MD simulations use force fields. Currently, classical force fields are widely used, but they have the disadvantage of not accounting for polarizability. Polarizability is crucial because it determines how easily the electron cloud of a molecule can be distorted, influencing intermolecular interactions and properties. Not including polarizability makes classical force fields less accurate. To address this issue, polarizable force fields (PFF) have been developed, providing a more accurate picture of the molecular environment.

Let us understand what force fields and polarizability are, and examine the advantages that PFF bring to MD simulations.

How do MD simulations work?

MD simulations can capture how atoms interact with each other, such as in protein-ligand binding. But how exactly does it work? At the heart of it all are force fields. These are sets of mathematical expressions based on physics and developed from our deep understanding of chemistry. They help capture the movements and energies of a molecular system. These expressions are integrated into algorithms, allowing us to solve force field equations quickly using computers. All molecular movements within a system are influenced by their neighbours and the constraints due to their own structure. So, if we understand these constraints and the surrounding environment, we can predict the movements of molecules. How cool is that?!

Let us breakdown force fields

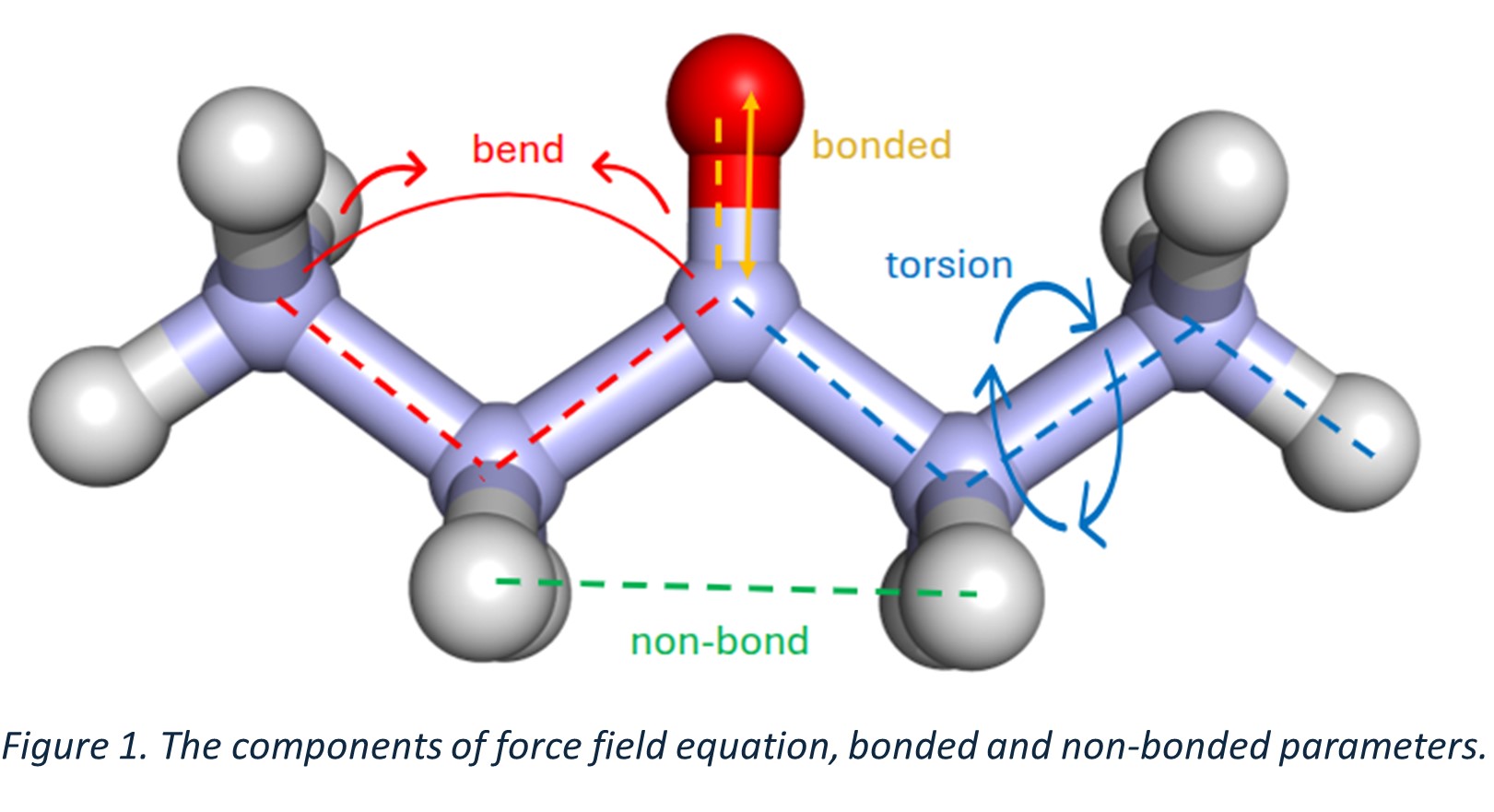

The movement of a molecule is not completely random; it's influenced by its intrinsic properties, much like how your body movement is influenced by biomechanics. Force fields can be broken down into bonded and non-bonded interactions. Bond stretching, bond bending, bond angles, and bond torsion make up the bonded interactions (Figure 1). Similarly, electrostatic and Van der Waals forces form the non-bonded interactions. Below is the general equation describing a force field.

E_MM=E_str+E_bend+E_tors+E_ele+E_vdw

Where represents potential energy of a system, is bond stretching, is bond bending, is bond torsion, is electrostatic, is vander waals energies. The force fields that contain these parameters are called classical force fields and are widely used in the field of simulations. However, these force fields have a limitation: they ignore one important interaction, polarizability. This makes their results less accurate. Polarizability is crucial because it determines how easily the electron cloud of a molecule can be distorted, influencing intermolecular interactions and properties.

Why was polarizability not accounted for?

During the development of these force fields, polarizability was ignored because its calculation brought a huge overhead in performance. However, with computers becoming more powerful, cheaper, and more efficient, it is now possible for us to include it.

What is polarizability?

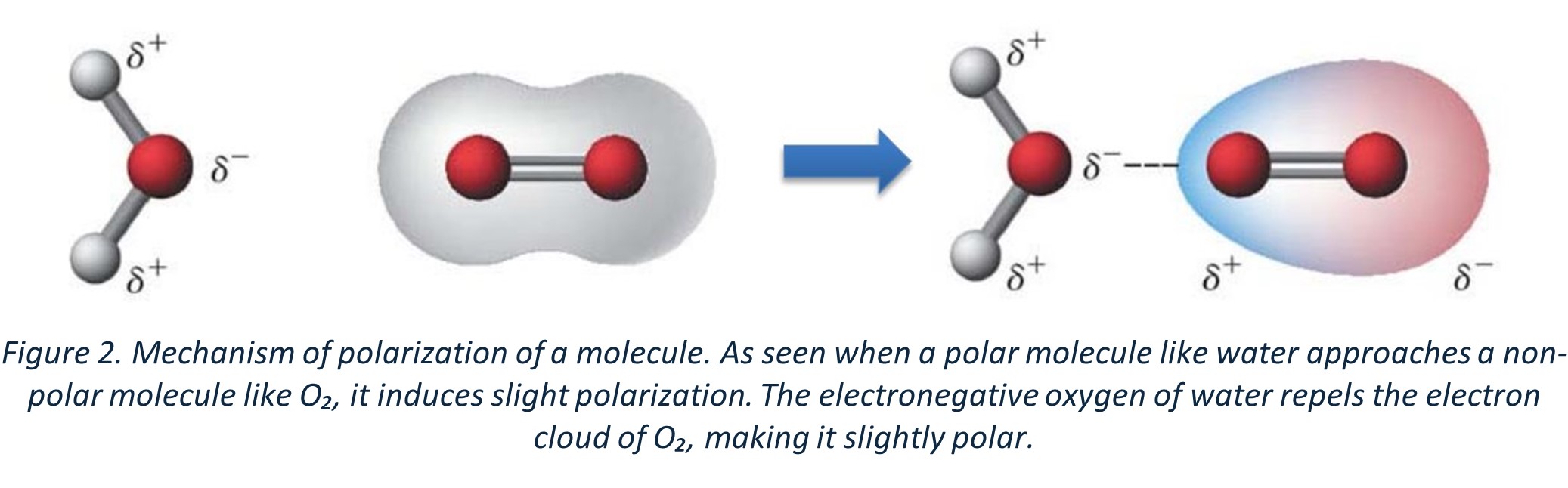

In some molecules, electrons are spread evenly, and these are called non-polar molecules. In others, like polar compounds (e.g., water), the electrons are already unevenly distributed. However, non-polar molecules can become slightly polar under the influence of an external electric field or neighboring polar molecules. This happens because, as a charged molecule approaches a non-polar compound, it repels or attracts the electron cloud based on the influence of this approaching charge.

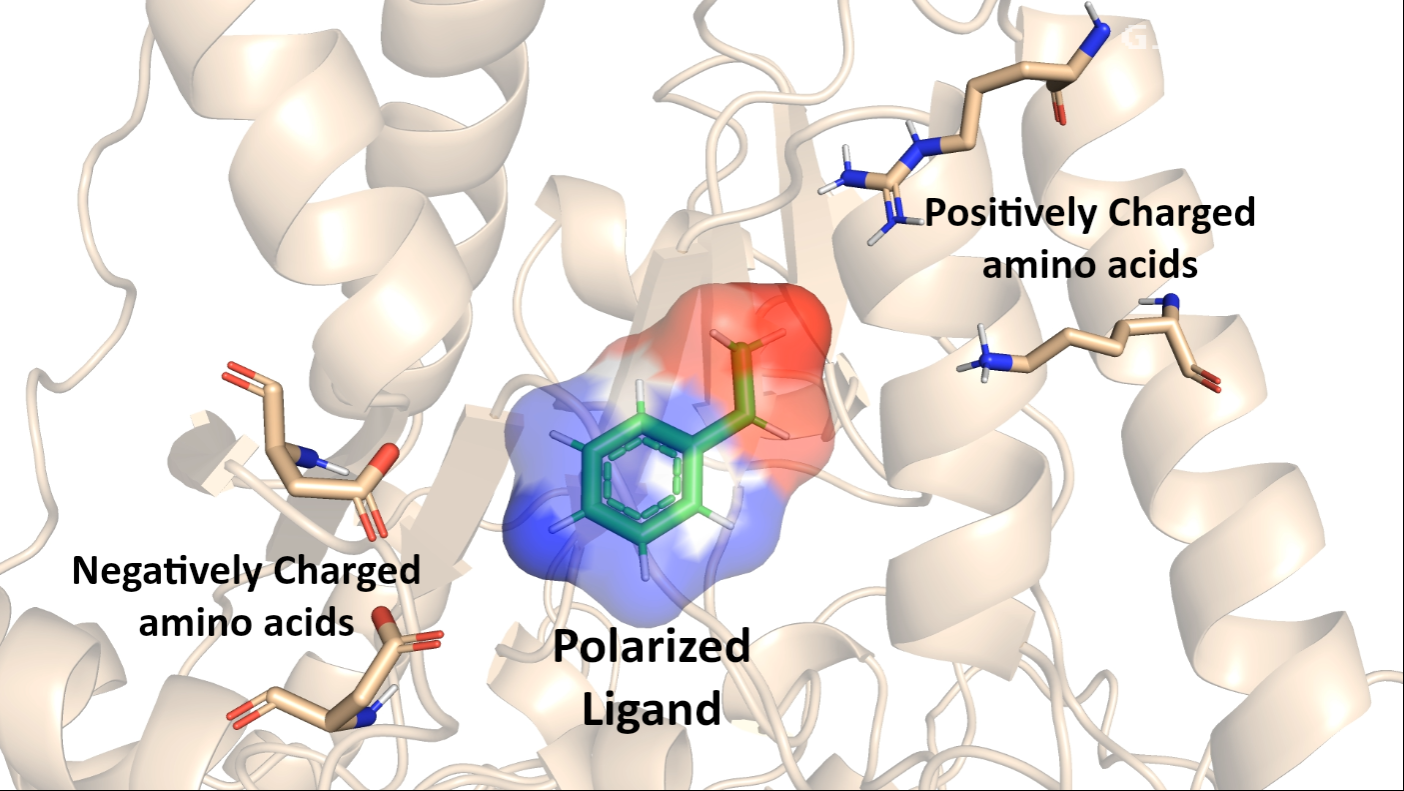

This effect of polarizability also occurs in amino acids. The polarizability of amino acids varies significantly, with tryptophan and phenylalanine being highly polarizable, while glycine and alanine exhibit low polarizability. This variation in polarizability leads to conformational changes in proteins as certain amino acids become polarized. Understanding and utilizing polarization in protein studies is crucial for accurately modeling these conformational changes and interactions.

Why go through all these hassles?

Why do we need to do all this extra work to include polarizability? It provides several advantages:

- Improved Water-Protein Interactions: Water is crucial in protein simulations because it is a polarizable medium. This means its molecules can reorient themselves in response to the electric fields generated by the protein.

- Better Charge Distribution: Charge distribution within a protein can greatly affect its binding affinity to other molecules. PFF account for the ability of atoms and molecules to redistribute their charges in response to their environment, providing a more accurate representation of these interactions.

- Drug Design: In drug design, understanding how a drug molecule interacts with its target protein is crucial. Better charge distribution models allow researchers to see how the protein's charges are distributed and how they change upon binding with a drug.

- Enhanced Protein Conformation Dynamics: Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are themselves polarizable molecules. This means their shapes and behaviors can change in response to their environment, leading to conformational changes in proteins.

All aspects things make it important to use polarization in Protein simulation.

How does Polarizable Force Fields account for polarizability?

The polarizability of a molecule is represented by partial charges, typically placed at the center of each atom. In classical force fields, these charges are static, meaning they do not account for polarizability. However, in PFF, the partial charges are dynamic and adjust according to the influence of the surrounding protein environment. This dynamic adjustment allows PPF to accurately capture the polarizability of molecules, leading to more precise simulations and insights into protein behaviour.

Types of Polarizable force fields?

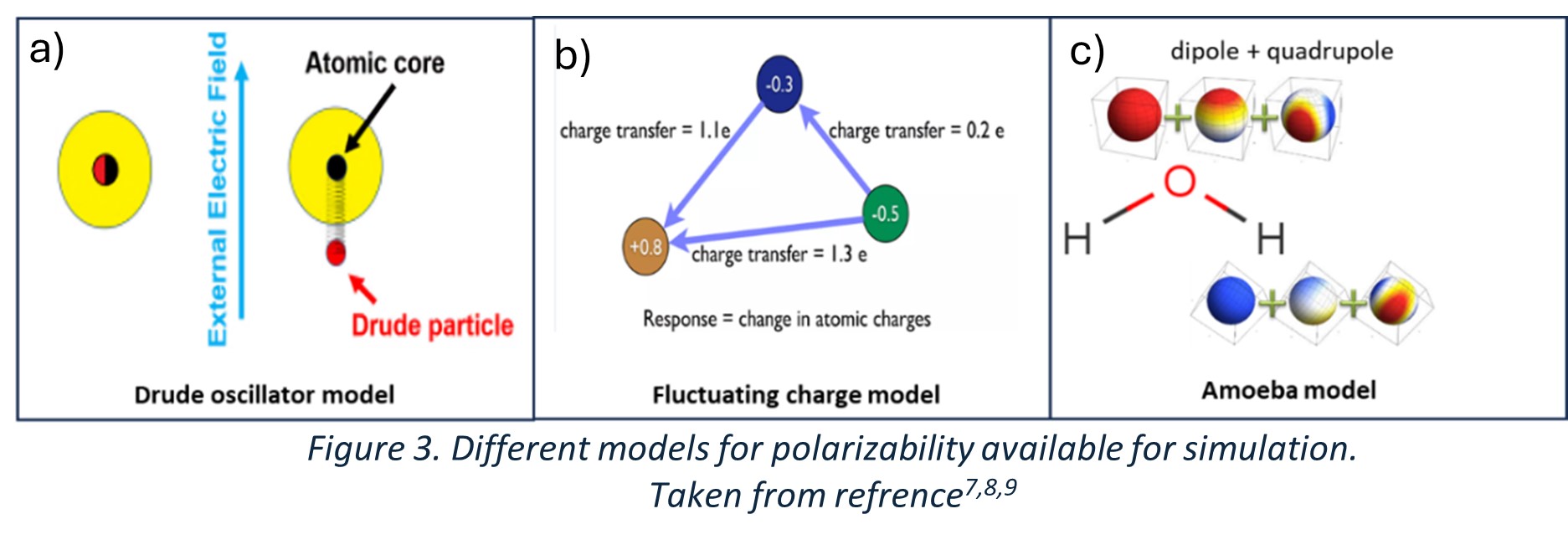

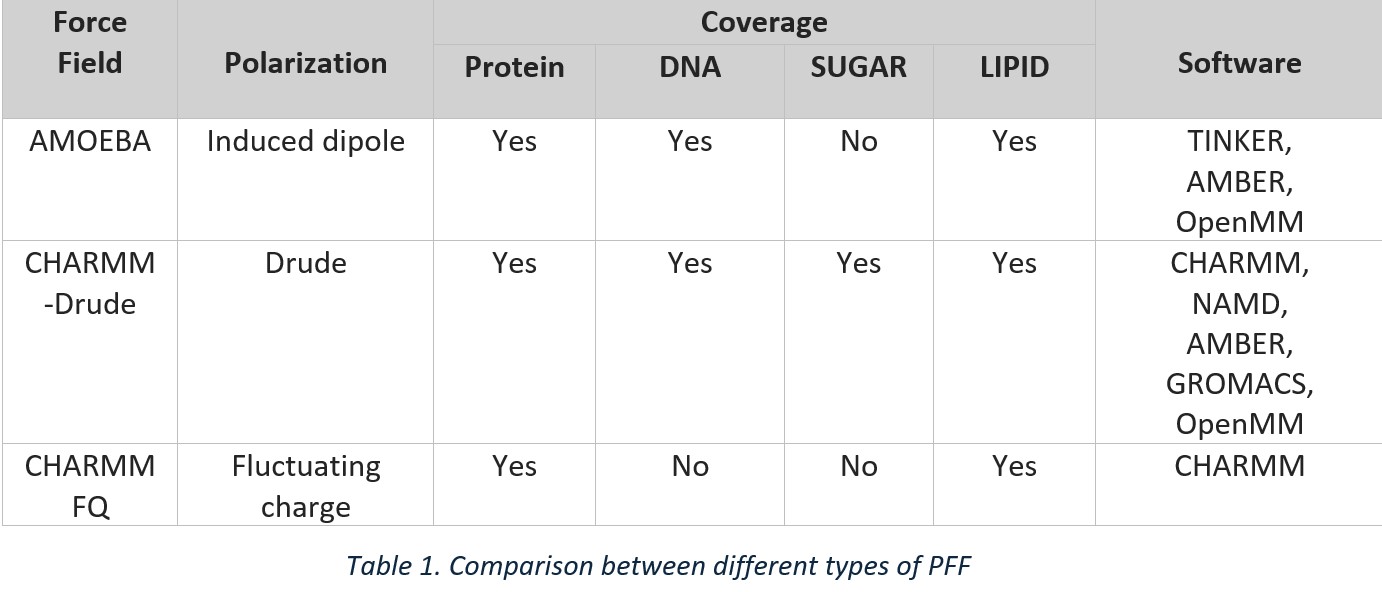

Various PPFs have now been developed to account for the polarizability of a system. Most notably, CHARMM Drude, AMOEBA, and CHARMM force fields. These force fields differ in how they represent polarizability. Let us now look at each one of them.

CHARMM Drude: A fictitious particle is attached to the atom using a harmonic spring to represent its polarizability. The displacement of the Drude particle is influenced by the local electric field, and reflects the induced dipole moment, capturing the system's polarization (Figure 3a).

CHARMM Fluctuating Charge Force Field: Atomic partial charges are dynamically adjusted based on the influence of neighbouring atoms. This is achieved through a self-consistent field (SCF) process, where charges are iteratively updated until the system reaches its lowest energy state (Figure 3b).

AMOEBA: This force field models polarization by combining fixed multipoles (monopoles, dipoles, and quadrupoles) with induced dipoles. This hybrid approach enables a more accurate representation of electrostatic interactions and charge distributions (Figure 3c).

So, what is stopping them?

If PFF offer so many advantages, why aren't they widely available yet? Here are some of the challenges:

- Computational Cost: Including polarizability introduces new calculations, significantly increasing computational costs. Simulations that previously achieved 100 nanoseconds (ns) may now only reach 10 ns or less

- Complexity in Parameterization: Parameterizing PFF is a complex and time-consuming process. It often requires fitting parameters to experimental data, which can be limited or inconsistent.

- Limited Community: PFF are relatively new and still in the experimental phase. As a result, only a few simulations have been reported so far. It will take time for the wider scientific community to adopt and standardize these methods.

- Software Limitations: Currently, popular software packages like GROMACS have limited or no support for PFF. This lack of implementation restricts researchers to using less familiar or less optimized software.

Case study

Improved Modelling of π-Cation and Ring- Anion Interactions using the Drude Polarizable Empirical Force Field

The π-Cation interactions are noncovalent bonds between a π-electron system and a positively charged ion. These are considered strong noncovalent forces and are commonly found in biological systems. Extensive research has shown that they are involved in protein systems, protein-DNA, protein-lipid, and protein-ligand complexes. They play important roles in structural stability, catalysis, molecular recognition, and ionic selectivity. They also contribute to the binding energy of ligands with aromatic rings in proteins.

Similarly, though less explored, anion-ring interactions also occur in proteins, along with in-plane interactions between anions and aromatic rings. Since these interactions involve a polarizing ion and a polarizable π system, classical force fields might struggle to accurately model them in MD simulations. This highlights the need for PFF.

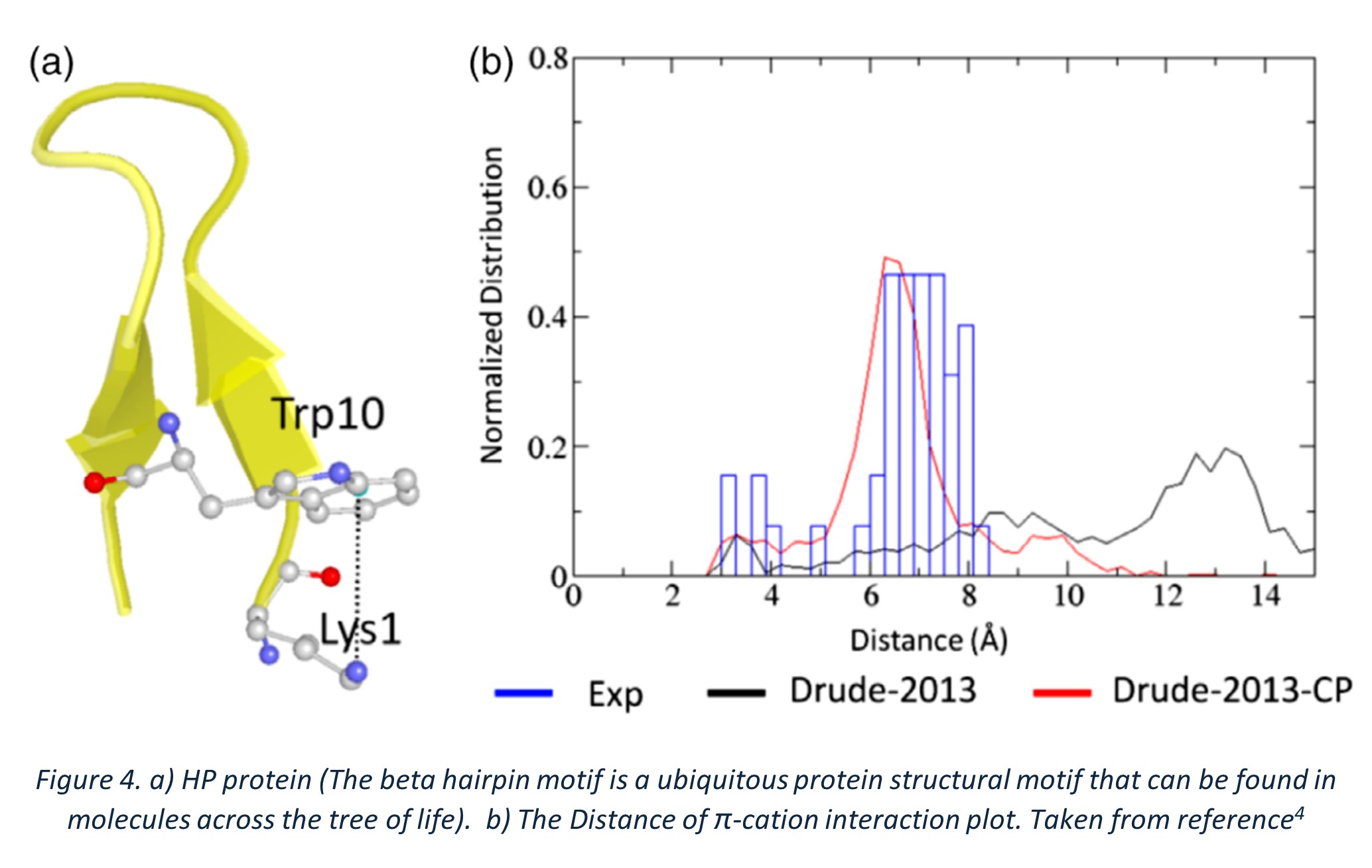

In this study, a 12-residue beta hairpin (HP, PDB: 2EVQ) was used, which contains a π-cation interaction between the Trp10 ring and the nitrogen of Lys1, playing a vital role in its conformation (Figure 4a). This interaction was used to assess the credibility of PFF. The distance of this interaction was analysed and compared between experimental data and the specially parameterized Drude-2013-CP force field. The histogram shown in the graph represents the NMR data, with the distance mainly in the range of 6-8 Å (Figure 4b). As we can see, the newly polarizable FF Charm Drude-CP was able to capture the interaction, correlating well with the experimental data (red line overlapping with the histogram). The normal Drude-2013 did not show significant correlation to the NMR experimental data and showed the distance above 10 Å, indicating that the interaction was not captured (black line).

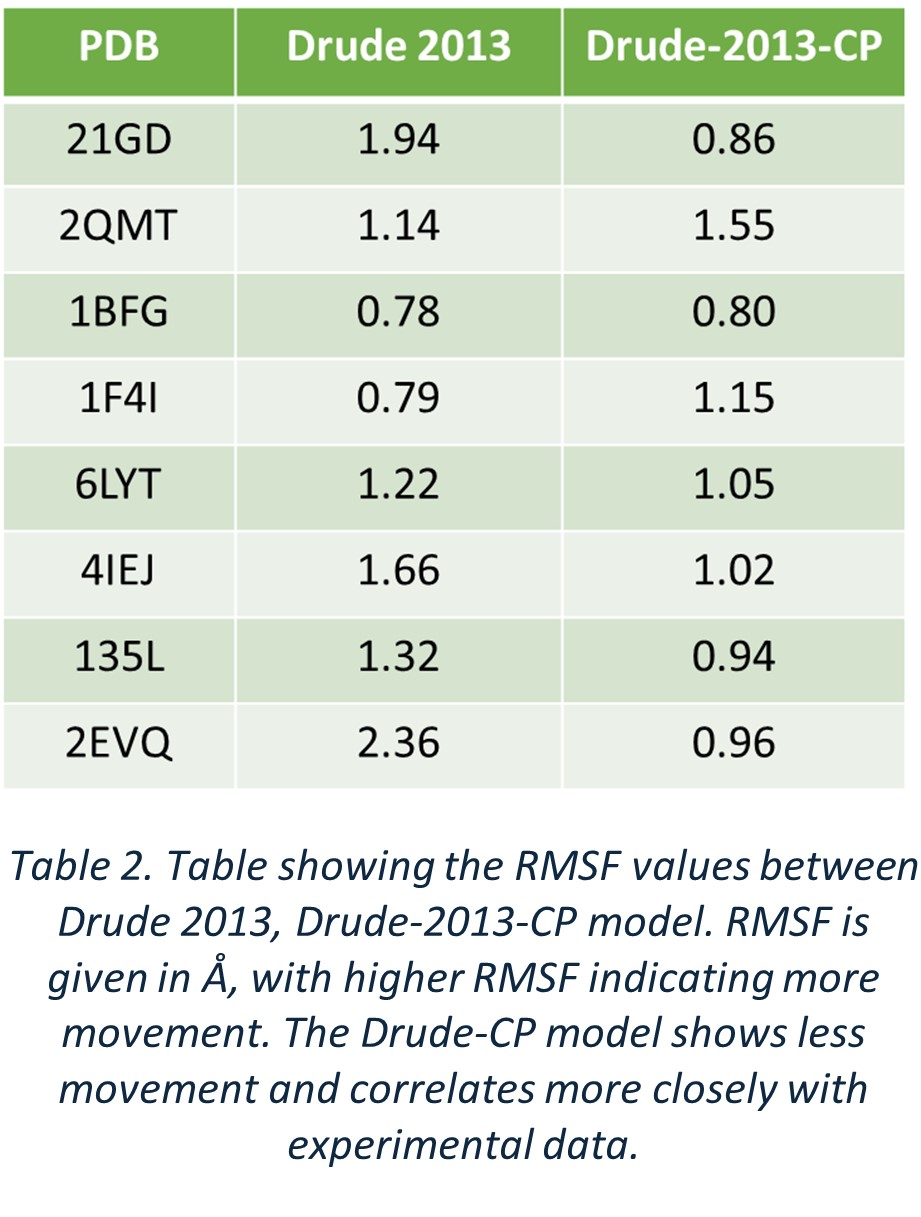

To further validate, RMSF values and structural data from both methods were compared. Results showed that Drude-2013 produced significantly higher values relative to experimental B-factors than those derived from Drude-2013-CP (Table 2).

The Future of Polarizable Force Fields

As computational power continues to grow, PFF are poised to become more mainstream. Their ability to enhance the accuracy of molecular dynamics simulations makes them a valuable tool for tackling complex scientific challenges. While the journey is still in its early stages, the promise of PFF in revolutionizing computational chemistry is undeniable.

References:

- González, M. A. (2011). Force fields and molecular dynamics simulations. Collection SFN, 12, 169–200. https://doi.org/10.1051/sfn/201112009

- Hollingsworth, S. A., & Dror, R. O. (2018). Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron, 99(6), 1129–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.011

- Ormeño, F., & General, I. J. (2024). Convergence and equilibrium in molecular dynamics simulations. Communications Chemistry, 7, Article 26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01114-5

- Lin, F.-Y., & MacKerell, A. D., Jr. (2019). Improved modeling of cation-π and anion-ring interactions using the Drude polarizable empirical force field for proteins. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 40(12), 1060–1069. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.26067

- Lemkul, J. A., Huang, J., Roux, B., & MacKerell, A. D., Jr. (2016). An empirical polarizable force field based on the classical Drude oscillator model: Development history and recent applications. Chemical Reviews, 116(9), 6341–6376. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00505

- Lindert, S., Bucher, D., Eastman, P., Pande, V., & McCammon, J. A. (2013). Accelerated molecular dynamics simulations with the AMOEBA polarizable force field on graphics processing units. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 9(11), 4684–4691. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct400514p

- Wei, Y., & Li, P. (2022). Modeling metal ions in enzyme catalysis. In Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821978-2.00019-2

- Chen, J. (n.d.). Polarization and charge transfer in classical molecular dynamics [PowerPoint slides]. Martínez Group, Chemistry, MRL and Beckman, UIUC. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/polarization-and-charge-transfer-in-classical-molecular-dynamics/470668#10

- SimTK. (n.d.). iAMOEBA, an Inexpensive AMOEBA Polarizable Water Model. Retrieved from https://simtk.org/frs/?group_id=847